Charlotte Geaghan-Breiner, Where the Wild Things Should Be: Healing Nature Deficit Disorder through the Schoolyard (student essay)

Title begins with a reference many readers will recognize (Sendak) and then points to the direction the argument will take.

Where the Wild Things Should Be: Healing Nature Deficit Disorder through the Schoolyard

CHARLOTTE GEAGHAN-BREINER

396

The developed world deprives children of a basic and inalienable right: unstructured outdoor play. Children today have substantially less access to nature, less free range, and less time for independent play than previous generations had. Experts in a wide variety of fields cite the rise of technology, urbanization, parental over-scheduling, fears of stranger-danger, and increased traffic as culprits. In 2005 journalist Richard Louv articulated the causes and consequences of children’s alienation from nature, dubbing it “nature deficit disorder.” Louv is not alone in claiming that the widening divide between children and nature has distressing health repercussions, from obesity and attention disorders to depression and decreased cognitive functioning. The dialogue surrounding nature deficit disorder deserves the attention and action of educators, health professionals, parents, developers, environmentalists, and conservationists alike.

Background information introduces a claim that states an effect and traces it back to its various causes.

Considerable evidence supports the claim.

Presents a solution to the problem and foreshadows full thesis

The most practical solution to this staggering rift between children and nature involves the schoolyard. The schoolyard habitat movement, which promotes the “greening” of school grounds, is quickly gaining international recognition and legitimacy. A host of organizations, including the National Wildlife Federation, the American Forest Foundation, and the Council for Environmental Education, as well as their international counterparts, have committed themselves to this cause. However, while many recognize the need for “greened school grounds,” not many describe such landscapes beyond using adjectives such as “lush,” “green,” and “natural.” The literature thus lacks a coherent research-based proposal that both asserts the power of “natural” school grounds and delineates what such grounds might look like.

397

The author identifies a weakness in the proposed solution.

Ending paragraph of the introduction presents the full thesis and outlines the entire essay.

My research strives to fill in this gap. I advocate for the schoolyard as the perfect place to address nature deficit disorder, demonstrate the benefits of greened schoolyards, and establish the tenets of natural schoolyard design in order to further the movement and inspire future action.

Author uses subheads to help guide readers through the argument.

ASPHALT DESERTS: THE STATE OF THE SCHOOLYARD TODAY

As a formative geography of childhood, the schoolyard serves as the perfect place to address nature deficit disorder. Historian Peter Stearns argues that modern childhood was transformed when schooling replaced work as the child’s main social function (1041). In this contemporary context, the schoolyard emerges as a critical setting for children’s learning and play. Furthermore, as parental traffic and safety concerns increasingly constrain children’s free range outside of school, the schoolyard remains a safe haven, a protected outdoor space just for children.

Explains why it’s valuable to focus on the schoolyard

Despite the schoolyard’s major significance in children’s lives, the vast majority of schoolyards fail to meet children’s needs. An outdated theoretical framework is partially to blame. In his 1890 Principles of Psychology, psychologist Herbert Spencer championed the “surplus energy theory”: play’s primary function, according to Spencer, was to burn off extra energy (White). Play, however, contributes to the social, cognitive, emotional, and physical growth of the child (Hart 136); “[l]etting off steam” is only one of play’s myriad functions. Spencer’s theory thus constitutes a serious oversimplification, but it still continues to inform the design of children’s play areas.

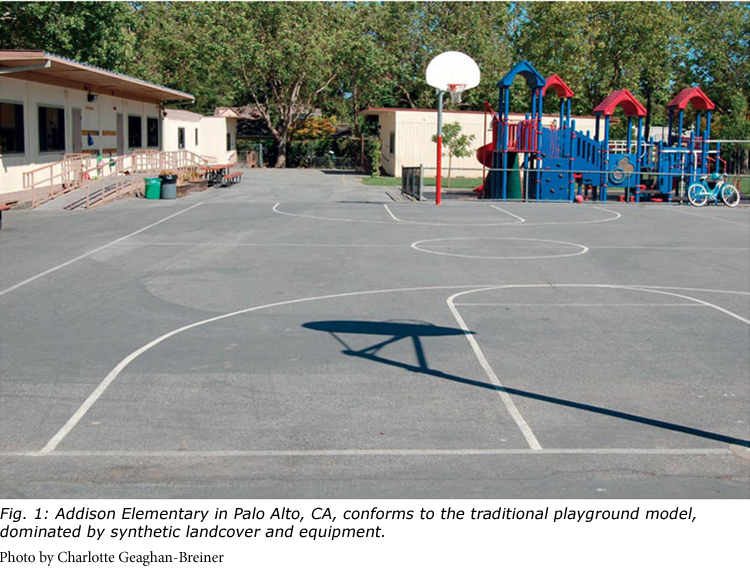

Most US playgrounds conform to an equipment-based model constructed implicitly on Spencer’s surplus energy theory (Frost and Klein 2). The sports fields, asphalt courts, swing sets, and jungle gyms common to schoolyards relegate nature to the sidelines and prioritize gross motor play at the expense of dramatic play or exploration. An eight-year-old in England says it best: “The space outside feels boring. There’s nothing to do. You get bored with just a square of tarmac” (Titman 42). Such an environment does not afford children the chance to graduate to new, more complex challenges as they develop. While play equipment still deserves a spot in the schoolyard, equipment-dominated playscapes leave the growing child bereft of stimulating interactions with the environment.

Quotations by children provide evidence to support the claim and bring in a personal touch. Note that the writer is following MLA style for in-text citations.

Presents reasons why schoolyards continue to be poorly designed

Also to blame for the failure of school grounds to meet children’s needs are educators’ and developers’ adult-centric aims. Most urban schoolyards are sterile environments with low biodiversity (see fig. 1). While concrete, asphalt, and synthetic turf may be easier to maintain and supervise, they exacerbate the “extinction of experience,” a term that Pyle has used to describe the disappearance of children’s embodied, intuitive experiences in nature. Asphalt deserts are major instigators of this “cycle of impoverishment” (Pyle 312). Loss of biodiversity begets environmental apathy, which in turn allows the process of extinction to persist. Furthermore, adults’ preference for manicured, landscaped grounds does little to enhance children’s creative outdoor play. Instead of rich, stimulating play environments for children, such highly ordered schoolyards are constructed with adults’ convenience in mind.

399

Note that the figure is introduced in the text and has a caption.

THE GREENER, THE BETTER: THE BENEFITS OF GREENED SCHOOL GROUNDS

Author cites research that discusses the health benefits of interacting with nature.

A great body of research documents the physiological, cognitive, psychological, and social benefits of contact with nature. Health experts champion outdoor play as an antidote to two major trends in children of the developed world: the Attention Deficit Disorder and obesity epidemics. A 2001 study by Taylor, Kuo, and Sullivan indicates that green play settings decrease the severity of symptoms in children with ADD. They also combat inactivity in children by diversifying the “play repertoire” and providing for a wider range of physical activity than traditional playgrounds. In the war against childhood obesity, health advocates must add the natural schoolyard to their arsenal.

The schoolyard also has the ability to influence the way children play. Instead of being prescribed a play structure with a clear purpose (e.g., a swing set), children in natural schoolyards must discover the affordances of their environment—they must imagine what could be. In general, children exhibit more prosocial behavior and higher levels of inclusion in the natural schoolyard (Dyment 31). A 2006 questionnaire-based study of a greening initiative in Toronto found that the naturalization of the school grounds yielded a decrease in aggressive actions and disciplinary problems and a corresponding increase in civility and cooperation (Dyment 28). The greened schoolyard offers benefits beyond physical and mental health; it shapes the character and quality of children’s play interactions.

400

Social benefits of interacting with nature

The schoolyard also has the potential to shape the relationship between children and the natural world. In the essay “Eden in a Vacant Lot,” Pyle laments the loss of vacant lots and undeveloped spaces in which children can play and develop intimacy with the land. However, Pyle overlooks the geography of schoolyards, which can serve as enclaves of nature in an increasingly urbanized and developed world. Research has shown that school ground naturalization fosters nature literacy and intimacy just as Pyle’s vacant lots do. For instance, a school ground greening program in Toronto dramatically enhanced children’s environmental awareness, sense of stewardship, and curiosity about their local ecosystem (Dyment 37). When integrated with nature, the schoolyard can mitigate the effects of nature deficit disorder and reawaken children’s innate biophilia, or love of nature.

BIOPHILIC DESIGN: ESTABLISHING THE TENETS OF NATURAL SCHOOLYARD DESIGN

The need for naturalized schoolyards is urgent. But how might theory actually translate into reality? Here I will propose four principles of biophilic schoolyard design, or landscaping that aims to integrate nature and natural systems into the man-made geography of the schoolyard.

The author establishes four guidelines for redesigning schoolyards.

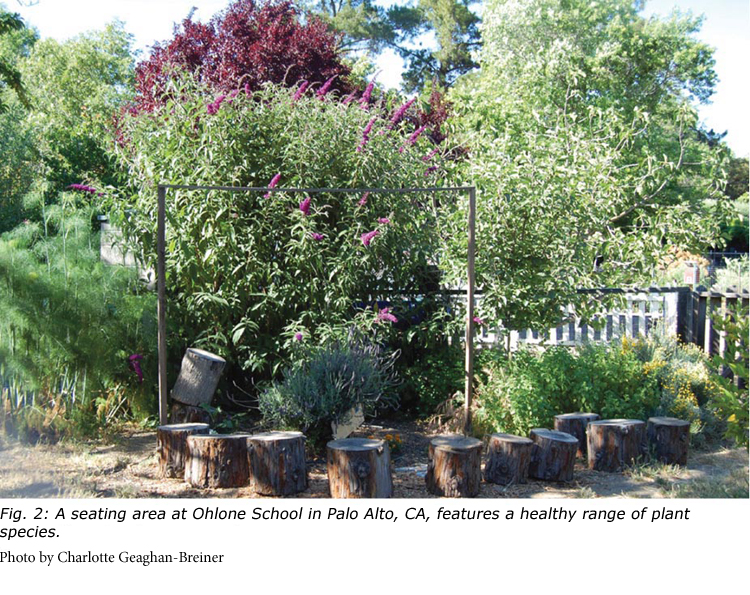

The first is biodiversity. Schools should strive to incorporate a wide range of greenery and wildlife on their grounds (see fig. 2). Native plants should figure prominently so as to inspire children’s interest in their local habitats. Inclusion of wildlife in school grounds can foster meaningful interactions with other species. Certain plants and flowers, for example, attract birds, butterflies, and other insects; aquatic areas can house fish, frogs, tadpoles, and pond bugs. School pets and small-scale farms also serve to teach children important lessons about responsibility, respect, and compassion for animals. Biodiversity, the most vital feature of biophilic design, transforms former “asphalt deserts” into realms teeming with life.

401

The second principle that schoolyard designers should keep in mind is sensory stimulation. The greater the degree of sensory richness in an environment, the more opportunities it affords the child to imagine, learn, and discover. School grounds should feature a range of colors, textures, sounds, fragrances, and in the case of the garden, tastes. Such sensory diversity almost always accompanies natural environments, unlike concrete, which affords comparatively little sensory stimulation.

Diversity of topography constitutes another dimension of a greened schoolyard (Fjortoft and Sageie 83). The best school grounds afford children a range of places to climb, tunnel, frolic, and sit. Natural elements function as “play equipment”: children can sit on stumps, jump over logs, swing on trees, roll down grassy mounds, and climb on boulders. The playscape should also offer nooks and crannies for children to seek shelter and refuge. While asphalt lots and play structures are still fun for children, they should not dominate the school grounds (see fig. 3).

402

A figure illustrates a specific point about play structures.

Last but not least, naturalized schoolyards must embody the theory of loose parts proposed by architect Simon Nicholson. “In any environment,” he writes, “both the degree of inventiveness and the possibility of discovery are directly proportional to the number and kinds of variables in it” (qtd. in Louv 87). Loose parts—sand, water, leaves, nuts, seeds, rocks, and sticks—are abundant in the natural world. The detachability of loose parts makes them ideal for children’s construction projects.

403

While some might worry about the possible hazards of loose parts, conventional play equipment is far from safe: more than 200,000 of children’s emergency room visits every year in the United States are linked to these built structures (Frost 217). When integrated into the schoolyard through naturalization, loose parts offer the child the chance to gain ever-increasing mastery of the environment.

The four tenets proposed provide a concrete basis for the application of biophilic design to the schoolyard. Such design also requires a frame-shift away from adult preferences for well-manicured grounds and towards children’s needs for wilder spaces that can be constructed, manipulated, and changed through play (Lester and Maudsley 67; White and Stoecklin). Schoolyards designed according to the precepts of biodiversity, sensory stimulation, diversity of topography, and loose parts will go a long way in healing the rift between children and nature, a rift that adult-centric design only widens.

GROUNDS FOR CHANGE

In conclusion, I have shown that natural schoolyard design can heal nature deficit disorder by restoring free outdoor play to children’s lives in the developed world. Successful biophilic schoolyards challenge the conventional notion that natural and man-made landscapes are mutually exclusive. Human-designed environments, and especially those for children, should strive to integrate nature into the landscape. All schools should be designed with the four tenets of natural schoolyard design in mind.

Author restates her claim.

Though such sweeping change may seem impractical given limitations on school budgets, greening initiatives that use natural elements, minimal equipment, and volunteer work can be remarkably cost-effective. Peninsula School in Menlo Park, California, has minimized maintenance costs through the inclusion of hardy native species; it is essentially “designed for neglect” (Dyment 44). Gardens and small-scale school farms can also become their own source of funding, as they have for Ohlone Elementary School in Palo Alto, California. Ultimately, the cognitive, psychological, physiological, and social benefits of natural school grounds are priceless. In the words of author Richard Louv, “School isn’t supposed to be a polite form of incarceration, but a portal to the wider world” (Louv 226). With this in mind, let the schoolyard restore to children their exquisite intimacy with nature: their inheritance, their right.

404

Offers examples of successful biophilic schoolyard design

WORKS CITED

Dyment, Janet. “Gaining Ground: The Power and Potential of School Ground Greening in the Toronto District School Board.” Evergreen, 2006, www.evergreen.ca/downloads/pdfs/Gaining-Ground.pdf.

Fjortoft, Ingunn, and Jostein Sageie. “The Natural Environment as a Playground for Children.” Landscape and Urban Planning, vol. 48, no. 2, Winter 2001, pp. 83-97.

Frost, Joe L. Play and Playscapes. Delmar, 1992.

Frost, Joe L., and Barry L. Klein. Children’s Play and Playgrounds. Allyn and Bacon, 1979.

Hart, Roger. “Containing Children: Some Lessons on Planning for Play from New York City.” Environment and Urbanization, vol. 14, no. 2, October 2002, pp. 135-48, eau.sagepub.com/content/14/2/135.full.pdf.

Lester, Stuart, and Martin Maudsley. Play, Naturally: A Review of Children’s Natural Play. Play England, National Children’s Bureau, 2007.

Louv, Richard. Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder. Algonquin of Chapel Hill, 2005.

Nicholson, S. “How Not to Cheat Children: The Theory of Loose Parts.” Landscape Architecture, vol. 62, October 1971, pp. 30–35.

Pyle, Robert M. “Eden in a Vacant Lot: Special Places, Species, and Kids in the Neighborhood of Life.” Children and Nature: Psychological, Sociocultural, and Evolutionary Investigations, edited by Peter H. Kahn and Stephen R. Kellert, MIT Press, 2002, pp.305-27.

Stearns, Peter N. “Conclusion: Change, Globalization and Childhood.” Journal of Social History, vol. 38, no. 4, 2005, pp. 1041-46.

405

Taylor, Andrea F., et al. “Coping with ADD: The Surprising Connection to Green Play Settings.” Environment and Behavior, vol. 33, no. 1, 2001, pp. 54–77.

Titman, Wendy. Special Places; Special People: The Hidden Curriculum of Schoolgrounds. World Wide Fund for Nature, 1994, files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED430384.pdf.

White, Randy. “Young Children’s Relationship with Nature: Its Importance to Children’s Development & the Earth’s Future.” Taproot, vol. 16, no. 2, Fall/Winter 2006, White Hutchinson Leisure and Learning Group, www.whitehutchinson.com/children/articles/childrennature.shtml.

White, Randy, and Vicki Stoecklin. “Children’s Outdoor Play & Learning Environments: Returning to Nature.” Early Childhood News, Mar. 1998, White Hutchinson Leisure and Learning Group, www.whitehutchinson.com/children/articles/outdoor.shtml.

Charlotte Geaghan-Breiner wrote this academic argument for her first-year writing class at Stanford University.